Commentary on the Critiques of the GRC Theory and the GRCS

In this section, I provide my comments about the critiques and feedback that I have received. Criticism, evaluation, and feedback are critical in understanding any new phenomena that has gone undefined and unexplored. I have encouraged critique because it is the best way to increase our understanding of GRC.

Mostly, I have appreciated the support of many colleagues in the psychology of men and other disciplines who worked diligently with the research and theory development. It has been a collaborative and generative process that I have enjoyed. I have appreciated the support from colleagues who believed that GRC was a reality in men’s lives. Additionally, SPSMM has been very supportive over the years sponsoring our annual symposia at the APA convention and giving GRC a home in the psychology of men.

GRC has been controversial and sometimes misunderstood. GRC was a new idea back in the late 1970s’ and so much of the early feedback was simply, reactionary and political. There was a fear that studying GRC would destroy the causes of Feminism and women’ liberation.

Most of the criticism has been helpful, but some of it has been misguided, uninformed, and competitive. I have responded to the criticism of GRC at APA conventions and in print (O’Neil, 2008; 2015; O’Neil & Denke, 2016) with more precise GRC definitions, conceptual models, and more elaborate research approaches.

Some critics have implied that the GRC models and research are simplistic and general; meaning not meeting sophificated research standards. For sure, the early GRC models were intentionally simple, so they could be first considered and understood. In this regard, “simple” was by design. Simplicity was necessary in the late 1970s’ given the resistance to these issues by men, some Feminists, and the status quo.

Like most visible measures, the construct validity of the GRCS has been evaluated. The consensus in the literature after many psychometric studies is that the GRCS has good construct validity with many different groups of men. Some very good suggestions to improve both the theory and the GRCS have been made in these critiques.

Other critiques have erroneously labeled GRC as a trait, when from its inception (O’Neil et al., 1986), it has been operationally defined as a psychological problem and situational dynamic that most men experience.

There have been definitional dilemmas with GRC. A lack of clarity has existed on how GRC is a different from masculinity ideology and conformity to masculine roles. Pleck (1995) stated that GRC is a co-factor of masculinity ideology and the research has shown this to be true. Moreover, GRC has been shown to be a distinct construct from masculinity ideology and conformity to masculine norms. For clarity, GRC focuses on psychological and behavioral conflict, not just masculine, ideological thinking or conformity to masculine and feminine norms.

Politically, GRC has been a triggering, polarizing concept and at times a divisive concept making it hard to gain rapid credibility (traction) in both psychology and the larger society. Nonetheless, GRC has continuously developed in psychology and other disciplines like student development, public health, nursing, medicine, and communication sciences.

In the early days, some Radical/Separatists Feminists erroneously equated the research program with justifying (i.e. condoning) men’s violence against women. The political climate then between men and women was very polarizing and politically charged because of widespread societal denial about men’s violence against women that Feminist were adamant about.

I remember saying to myself “We were not justifying men’s violence, but doing the opposite: documenting how restrictive gender roles contribute to men’s violence toward women so it could be prevented in the future”. GRC was difficult for many to understand because it was new, and not considered before. I moved past my defensiveness about some of the feedback and just listened, took notes, and accepted the criticism and confrontations as part of the research process and the promotion of social change.

In 1983, Playboy magazine ran a ridiculing, devaluing, defensive statement about GRC titled “So you think you got problems fella”. They made fun of my list of men’s GRC patterns published in The Counseling Psychologist. and verified that I was “poking at the patriarchy” by explaining GRC. This was more evidence that that GRC really did stimulate the patriarchy and status quo and therefore something for me to vigorously pursue.

There was considerable “push back” when I asked the question “Are men victims of sexism?” during a APA convention symposia in 1991 in San Francisco (Brooks, 1991 O’Neil, 1991). One of the discussants, a prominent Feminist in psychology, criticized my question and labeled it as polarizing and unfortunate. I was told to “back off” with my question about whether men were victim of sexism. Actually, I did not say that men were victims of sexism but only asked if it was a relevant question to have a feminist psychology of men.

Backing off from a critical question is something I rarely do and the notion of men as victim of sexism is still a relevant question for me.

Fortunately, over the years the victimizing effects of sexism and GRC in men’s lives has become more accepted. Now, gender role trauma strain (Pleck,1995) is recognized as a developing concept in the psychology of men. Studies on GRC and PTSD, trauma, and other oppressions provide some initial evidence that GRC does interact with men’s extreme stress and feeling discriminated against by others.

Another kind of critique was personal from other men in academia and in my social circle. There were jokes, insults, innuendo, homophobic reactions, and curiosity about what I was studying. Many of the men knew that my research was about them and I observed an uneasiness laced with defensiveness, homophobia, distain, and personal devaluation. These men did not like what I wrote, my advocacy for women or men, and sometimes my company. These men’s projected fear about GRC was directed at me but there was little comment on the actual ideas. These personal dynamics had to be processed and transformed into compassion for these men and positive action.

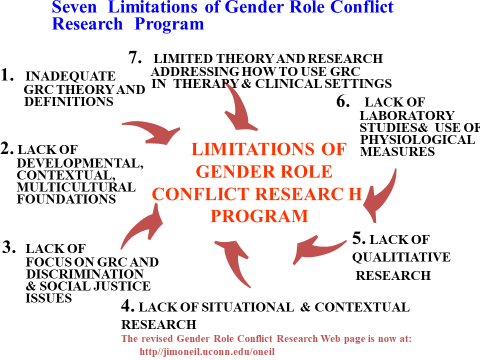

The diagram below depicts some of the limitations of the GRC research program and is discussed in the second introductory video lecture and in O’Neil (2015).